|

Project Structure and Financing of Green IPPs in SEA

- by Jessie L. Todoc, Pierre Cazelles, Jean-Marc Alexandre, Thierry Lefevre; CEERD, Thailand

and Susanne Schindler; University of Karlsruhe, Germany

Introduction

The active promotion of Green IPPs in Southeast Asia started in the Philippines with Executive Order 215 in 1987, allowing private sector participation in power generation including from renewable energy sources, and the Mini-Hydro Incentives Act in 1991, allowing construction and operation of mini- and small hydropower by the private sector. In 1992, Thailand launched the small power producers (SPP) program to connect to the grid power plants under 90 MW. In 2002, to encourage more Green IPPs, the program selected 31 renewable SPPs (mostly using biomass) to receive tariff subsidies. Malaysia and Indonesia recently launched similar programs following the success of the SPPs in Thailand. In Malaysia, the Small Renewable Power program (SREP) was launched in May 2001 to promote grid-connected renewable energy. The program will buy renewable energy capacity under 5 MW on a "willing seller, willing buyer, take and pay" basis. In Indonesia, the Small Power Purchase Law announced in June 2002 guarantees purchase by PLN, the national utility, of electricity generated by small power producers up to 1 MW using non-conventional energy sources.

From corporate to project finance

Corporate (or on-balance sheet) finance is the traditional means of financing investments. It involves issuance of shares of stocks or bonds or internal reserves, but in most cases raising debt based on the full corporate strength of the borrower at a price that reflects the creditworthiness of the borrower [Gonzales and Carlos, 2002]. Project finance, on the other hand, is a means of raising fund in which equity shareholders rely primarily on project revenues for their return on investment and creditors, for interest payments and recovery of principal. In principle, projects developed in the framework of project finance rely more on the creditworthiness of the project than the creditworthiness of the sponsors.

Thailand�s introduction of tariff subsidies for new renewable SPPs has caused a shift from the traditional corporate (or balance sheet) finance to the more innovative project finance in new projects that could be indicative of parallel trends in the other countries in the Southeast Asian region. The high availability of renewable energy resources�biomass (including agro-industrial residues), hydropower, and wind�and the supporting policies to promote their exploitation and development are both driving this trend (see previous issues of the GrIPP-Net News).

Since the Small Power Producers (SPP) program of Thailand started about 10 years ago, 23 of the 50 projects selling excess power to the national grid have run on renewable energy (mostly from bagasse).*

* However, the total installed capacity of these renewable SPPs represents only 15% of the total from the 50 SPPs. Moreover, only three of these 23 renewable SPPs have firm contracts with the national utility, that is, receiving both energy and capacity payments for a contractual period of more than five years. The rest have non-firm contracts, that is, receiving energy payments only for a contractual period of less than five years.

Seventeen of the 23 renewable SPPs currently operating and selling to the grid are bagasse-fired power plants. These have a total installed capacity of 365.5 MW and selling to the grid 88.7 MW. According to a study commissioned by the then National Energy Policy Office (NEPO, now EPPO, Energy Planning and Policy Office under the new Ministry of Energy), sugar mills are usually inefficient in producing energy, as their power requirements are small compared to the amount of energy their bagasse can produce [Hvid and Timilsina, 1998]. The SPP program opened opportunities for efficiency improvements financed by electricity sales.

The typical structure of a power plant that is fuelled by bagasse supplied by an adjacent sugar mill is shown in Figure 1.1. The power plant, which is owned by and integrated to the sugar mill, produces electricity and heat for the sugar mill and sells excess electricity to the grid. Based on the interviews conducted, since the start of the SPP program the sugar mill has invested on efficiency improvements on the power plant to be able to sell excess electricity to the grid. These investments are usually financed by corporate borrowings from local commercial banks at the rate of 50 to 100% of the investment costs; the difference is financed from the sugar mill�s balance sheet or internal cash generation. In Thailand, banks lend to their agro-industrial customers to finance investments in renewable power projects based on their long-term relationship with their client and not exactly on the merit of the project.

Figure 1.1. Structure of balance-sheet financed Green IPP

In 2001, the government called for bids for 300 MW from renewable SPPs that will receive 5-year tariff subsidy of up to Bt0.36 per kWh (0.9 US cents/kWh) sold to the grid. The following year, the government approved in principle 31 projects (out of more than 50 proposals) that would receive the tariff subsidy. These projects have a total installed capacity of more than 800 MW and would sell to the grid around 500 MW. Twenty of these 31 projects are designed to have firm contracts.

The recent round of tariff subsidies created opportunities for setting up special project companies that will develop the power plant in the framework of project finance. The 5-year tariff subsidies averaged Bt0.15-0.18 per kWh and amount to almost Bt3 billion (USD71 million). The project developers and sponsors interviewed said that the tariff subsidy would not significantly improve project IRR or ROE considering the much longer contractual period of 20-25 years (power purchase agreement or PPA). However, the subsidy will provide much needed cash relief during the first five years of the project.

With the subsidy, two distinct basic project structures have emerged as far as fuel supply is concerned. The first is shown in Figure 1.2. In this case, the special project company that will develop the power plant is put up by the sugar mill or rice mill that will supply all its residues to the power plant in exchange for steam and electricity sales; excess electricity is sold to the grid. To finance the project, the biomass mill provides the equity portion, while debt is provided by local commercial banks. The typical debt-to-equity ratio for this kind of project is 3:1.

Figure 1.2: Structure of project financed Green IPP supplied by a single biomass mill

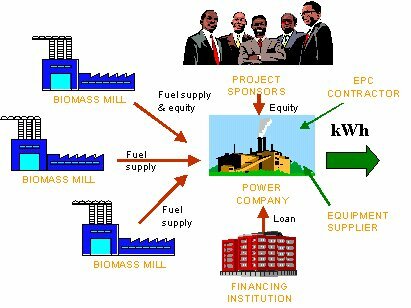

The second arrangement consists of a special project company put up by a project developer, this time dissociated from a biomass mill but with some experience in power project development. In this case, fuel supply is arranged with a number of biomass residue producers that in some cases also hold a small equity portion in the project. This project structure is illustrated in Figure 1.3. Local financing institutions provide up to 70-80% of investment costs. In Thailand, for example, Gulf Electric, which has an interest in a controversial coal IPP, and Asia Plywood Co. are developing a 23-MW rubber wood residue plant in southern Thailand. The two companies created a special purpose company called Gulf Yala Green to undertake the project. Asia Plywood will supply about 40% of the fuel requirements of the power plant through a subsidiary, Yala Waste, that in turn will have fuel supply agreements with other sawmills to supply the remaining wood residue requirements. Gulf Electric and Yala Waste will provide the 30% equity financing, while Gulf Electric is talking with a local bank for the remaining 70%. In Malaysia, Bumibiopower Holdings joint ventured with a palm oil mill to develop a 5.2-MW palm oil waste-fired power plant in Perak. The joint venture company will provide 25% of project cost as equity contribution, while the remaining 75% will be borrowed on "limited time full recourse" basis from local banks.

Figure 1.3: Structure of project financed Green IPP supplied by many biomass mills

Financing Green IPPs

Despite the policy push in many countries in SEA to promote Green IPPs (and the positive developments in Thailand following the announcement of the tariff subsidy), financing remains among the biggest hurdle in the development of Green IPPs [Lacrosse, 2002]. For example in the Philippines, the financial setting is not supportive to small and mini-hydro project development: long-term loans for this kind of projects are not available, the rates applied by development banks are near commercial rates, and commercial banks charge even higher rates and require parent company guarantee [Ronquillo, 2002]. The reasons are interrelated. Firstly, developing renewable energy or Green IPP projects remains more expensive than conventional power projects. For example, the project design document of the 23-MW rubber wood residue plant in Yala, Thailand, says it costs more to develop the Green IPP project than a conventional power project five times its size.

Secondly, there is limited experience in developing Green IPP projects. EC ASEAN Cogen interviewed a few project developers/sponsors and financial executives in Malaysia and Thailand, and most of those interviewed cite the lack of expertise in packaging this kind of projects and unfamiliarity with the renewable energy technology as the most important barriers in the development and financing of renewable energy projects [Gonzales and Carlos, 2002]. On one hand, small-scale project developers lack the in-house expertise to look for funds, prepare the financial plan of the project, and negotiate with lenders to obtain the most favourable financing terms. On the other hand, financial institutions lack the human resource and experience in evaluating renewable energy projects. For example, commercial banks in Thailand have been involved with conventional IPP projects but lack "real" exposure in renewable power projects developed in the framework of project financed.

Thirdly, obtaining financing for Green IPPs is not easy because of the persistent perceived and real high risks associated with biomass fuels in particular and to a lesser extent "real" risks of renewable energy technology in general. Banks, for instance, prefer that fuel suppliers take equity stakes in the project or that project sponsors themselves are the source of the renewable energy fuel like agricultural residues. One source of this perception is the difficulty in transporting this fuel especially if it comes from several fuel suppliers. Another is the seasonality associated with biomass fuels like agricultural residues, the productiion of which is not steady throughout the year or not all year-round.

The main motivation in lending to Green IPP projects is the long-term relationship banks have established with their clients, which decided to undertake a Green IPP. To minimize the risks associated with fuel supply, financial institutions require long-term fuel supply contracts.

However, the ease or difficulty in securing long-term fuel supply contract tends also to depend on the structure of the project. Securing long-term fuel supply contract is not a problem in situations where the power project is supplied by fuels exclusively from a rice or sugar mill that put up the power plant for its own consumption of electricity and steam and to earn extra revenue from selling excess electricity to the grid. Complications arise when project developers have to deal with independent fuel suppliers. The complications are magnified when project developers have to deal with many biomass residue producers. One rice-husk power developer interviewed, for example, has to deal with more than 100 small-, medium, and large-scale rice mills. To date, negotiations with these rice millers have already run to six years! But even dealing with few fuel suppliers remain a challenge because of their lack of experience in forging a long-term fuel supply contract that requires steady a supply of the biomass residues from eight to 25 years. According to the developers interviewed, instead of putting penalties for non-compliance or non-delivery of residues, they establish good and firm relations with fuel suppliers. The large-scale mills are invited to invest in the power project in terms of equity stakes, even minimal, in the special project company. Giving the fuel suppliers a sense of ownership will hopefully minimize the risk of unsteady fuel supply.

CDM�a financing opportunity?

In theory, the clean development mechanism (CDM) has been conceived to offer financing relief for energy projects, among others, that are otherwise unattractive for private financing. Through the CDM, emission reductions generated from Green IPP projects can be sold and provide additional cash inflows to the project that can cover a portion of the financing requirements. And the market for selling "carbon credits" is rapidly developing at the moment. In principle, emission reduction sales, depending on the price of carbon reductions, can also increase the financial performance or viability of the project.

In Thailand, at least three Green IPP projects are serious candidates for CDM. They are in the process of project validation, a step in the CDM process. One is the 23-MW Yala rubber wood residue plant that would sell 60,000 tonnes of CO2 (tCO2) per year; another is the 48-MW Mitr Phol bagasse power plant that would mitigate 270,000 tCO2 per year; and the third is the 5x22 MW A.T. Biopower rice husk power project that would sell 430,000 tCO2 per year.

Banks, however, do not count the cashflow from the sale of emission reductions in evaluating few projects that are up for CDM evaluation. Most investors are also not counting the potential for revenue from the sale of carbon credits. For them, the prospect for CDM remains blurred to be seriously considered. Those that did are backed by project sponsors that want to gain experience in CDM, but not really to benefit from it financially. In Thailand and in some other countries, there is still uncertainty as to the government�s stand on CDM, causing investors to downplay, if not ignore, its potential.

References

Electric Power Development Co. "Project Design Document for the Rubber Wood Residue Power Plant in Yala, Thailand," August 2002. DNV. <http://www2.dnv.com/certification/ClimateChange/Projects/ProjectDetails.asp?ProjectId=46>. (17 Feb. 2003)

Gonzales, Alan Dale C. and Carlos, Romel M. "Financing Issues and Options for Energy Efficiency, Renewable Energy and Greenhouse Gas Abatement Projects in Asia," paper written for The Second World Congress of Environmental and Resource Economists, 24-27 June 2002, Monterey, California

Hvid, Joergen and Timilsina, Govinda. "Evaluation of the SPP Regulation in Thailand." In NEPO/DANCED Investigation of Pricing Incentive in a Renewable Energy Strategy, a report prepared for NEPO, Oct. 1998. <http://www.eppo.go.th/encon/encon-DANCED.html>. (17 Feb. 2003)

Lacrosse, Ludovic. "Investing in Renewables," presentation at the 4th ASEAN Energy Business Forum, Bangkok, 21-22 Oct. 2002

Mitsubishi Securities, "Project Design Document for A.T. Biopower Rice Husk Power Project," January 2003. DNV. <http://www2.dnv.com/certification/ClimateChange/Projects/ProjectDetails.asp?ProjectId=52>. (17 Feb. 2003)

Personal interviews with executives from Thai organizations (A.T. Biopower, EGCO, Gulf Electric, CEC Co., Ratchaburi Holdings, EC ASEAN Cogen, Biomass One-Stop Clearing House (BOSCH) and the Energy-for-Environment Foundation, EPPO, Siemens, Enprima, Alstom Power, IFCT, Rabobank, Bangkok Bank). Feb.-March 2003.

Ronquillo, Rene. "Financing Small-Scale Hydropower Development in the Philippines," presentation at the First Regional Workshop of the ASEM-Green IPP Network, Bangkok, 24-25 Oct. 2002

Acknowledgement

This article is based largely on interviews with key project developers and sponsors, financial institutions, equipment suppliers, and energy institutions in Thailand. The authors sincerely acknowledge their generous accomodations and for sharing their expert knowledge, experience, and time. The usual disclaimer applies.

|